We Are Not NumbersAt the beginning of every school year in Gaza, I try to get off to a fresh start with my new students. I anticipate meeting a new group of girls with whom I will work—a new group of young women who will learn from me and I from them. I teach English language and most of my students are in their 20s, although some are fresh high school graduates.

I make this conscious “new beginning” for two reasons: First, to stoke my internal energy, passion and motivation. And secondly, to make a good impression on my students, so they will feel at ease at the beginning of the new year. This is especially important since the environment in Gaza is uninviting and depressing. I also keep in mind that each girl comes from a different background and has in one way or another been impacted by the volatile and precarious conditions of living in Gaza─ the aggressions, the blockade, the unpromising future.

Two years ago, I learned that one of my students had witnessed the killing of her aunt’s entire family during the 51-day Israeli aggression of 2014. Another had lost her fiancé and a third had lost her grandmother, two uncles and their families in one aerial strike. I constantly remind myself that I must treat my students with special care because they are victims of an Israeli-imposed occupation, aggression and blockade. They don’t possess supernatural powers that make them impervious to the endless number of obstacles—from bans on travel for any reason, to on-and-off attacks on or borders, to daily power cuts. It’s easy to give up and become like so many people here, which ultimately means death of the heart and soul.

When your dream is to flee

So, at the beginning of the year, I ask my students to tell me their hopes and dreams. Many, if not all, say they wish to travel for at least a short period; others to leave Gaza for good; and some will only say they have dreams but can’t accomplish them because they live in Gaza. For three consecutive years, I’ve heard my students repeat the same things, blaming Gaza for their misery and loss. They view it as a quagmire in which they are stuck and must await someone to save them.

The first meeting with my students is usually informal. I expect to hear their negative and passive comments about life in Gaza, so I make sure to start on a positive note. I don’t have a magic wand, so typically, only a few will respond to my efforts—realizing they have some control over their attitude and deciding to take the initiative. If you ask them, why they decided to take this course, their answer is always “to get a job.” It’s all about finding a job, getting married, raising children. But I insist on asking them: “What about your passion?”

Discovering your passion

I discovered my own passion—the written word—around the age of 12. I used to buy diaries and write in them at the end of each day. I also wrote poetry as I babysat our next-door neigh

I discovered my own passion—the written word—around the age of 12. I used to buy diaries and write in them at the end of each day. I also wrote poetry as I babysat our next-door neigh

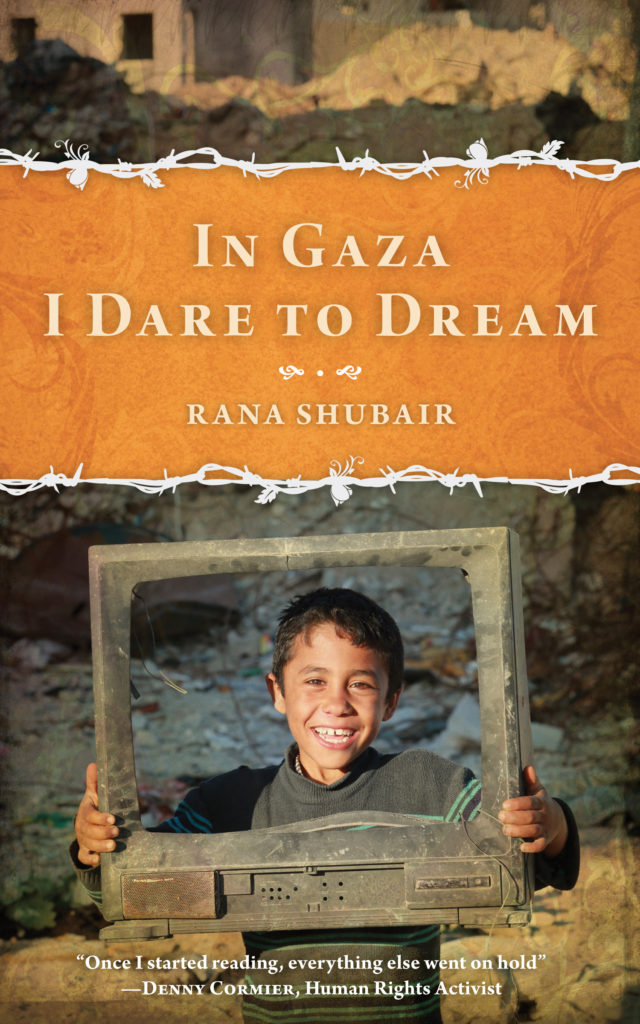

bor. I dug my nose into books, which were my favorite form of amusement back then; I never became bored when I always had “just one more chapter” to read. Reading and writing helped me create a world for myself that protected me throughout the turbulent phases of my life. (Last year, I published my own book, “In Gaza, I Dare to Dream.”)

It saddens me when many of my students say they don’t have dreams to fulfill because they’ve given up on them. The inhumane circumstances under which we live have crushed the people’s souls and sense of direction in life. We all read stories of challenge and courage in which people fight hard to accomplish their dreams, but it’s not the same for the young people of Gaza. It’s normal to face obstacles in life, but not in every single step you take. It’s like going from onestreet to another, only to find they’re all dead ends.

For those who need or wish to travel to pursue their education (many areas of study are not available in Gaza), few options lie ahead of them. With the intermittent and unreliable opening of the Rafah crossing into Egypt, many students have lost their scholarships. The other crossing that leads out of the Gaza cage is Erez, controlled by the Israeli occupation forces. But that is a totally different story (sigh).

The fragility of dreams

As a person living in besieged Gaza, the downside of having a dream is that it can easily be killed. In addition to all of the other obstacles, there is no room in the minds of most people here for innovation, creativity and wild dreams. Young people tend to see the dark side of their living situation, which is quite dreary.

The few exceptional people I’ve met who are creative in something are those who have a true passion that drives them. Plus, educational institutions largely focus on book-learning; there’s very little time given to extracurricular activities, critical thinking or creativity. The result is that teachers struggle to finish the curriculum in the designated time period and students, including children, labor to stuff the information into their brains by memorizing texts that are mostly way over their heads. As a mother of three 11-year-olds (triplets!), I’m confounded by my kids’ textbooks, which teach them the members of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (National Council, Executive Committee, blah blah blah). Why not also take them on field trips so they can feel, touch and see the natural beauty, for example? They might be inspired by the beauty of the seagulls at the Gaza port and then be inspired to learn more about these creatures. Why not take them to public institutions so they can see how real life is run?

Another reason for the lack of dreams is that fulfilling the basic needs of everyday life are an enormous challenge, dominating the minds of parents: how they can afford to support their families, secure an education for their children and obtain necessary health care. There is no time or justification for art or other forms of creativity—much less wild dreams.

The freedom of options

In many parts of the world, people are mentally and financially able to quit their jobs to pursue their passions. I’ve read many stories of people who have left their secure lives because they were boring and uncreative and instead took a risk to pursue their passion. And they are celebrated for this! After all, it’s part of their daring nature, their society says.

In Gaza, however, such a life-fulfilling step would be a death sentence. It’s common to find an employee who has been in the same job for 20 years without complaining about the mind-numbing routine. To this person, his/her job is a blessing that many other Gazans can only wish to have. (Unemployment is more than 40 percent, and higher among youth.) As for employees of international NGOs, they are viewed with an envious eye. They are the ones who live happily and stably. Nothing worries them except when they will get their next promotion. They make enough money to feed more than a dozen people, so you have to be exceptional to land a job in any international NGO.

In the end, I can emphatically say that yes, my people have dreams. They want to put their children to bed knowing they will wake up to the sound of birds, not bombs. The youth yearn to be given the chance to build a future with options and help their country thrive like any other people. In simple terms, they wish to be granted their basic human right to a life with dignity, peace and freedom so their dreams can be nurtured and even achieved.

Originally published on We Are Not Numbers